Stop. Rewind. Play.

It’s been close to 15 years since American military forces, in 2001, attacked Afghan soil in a war to remove the Taliban from political control in Afghanistan. The United States Government fought to gain control over the Afghan Government and appealed to the interests of several prominent Afghan tribal leaders in an attempt to establish a new Afghan Government. The americans rolled out the red carpet for the international donor and NGO community to make Kabul one of the hottest places on the map for humanitarian aid, business interests, and a bucket list of international agendas. What can we learn now about the decisions that poured into Kabul's urban plan in the last 15 years?

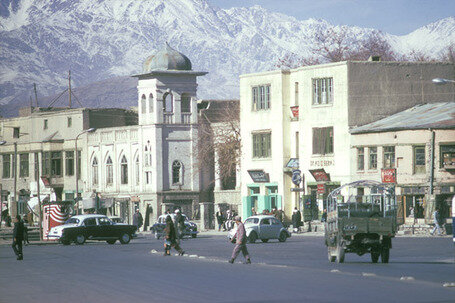

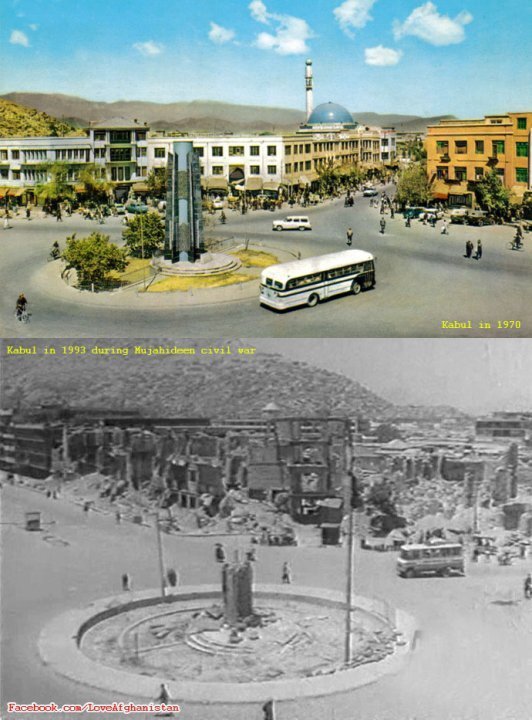

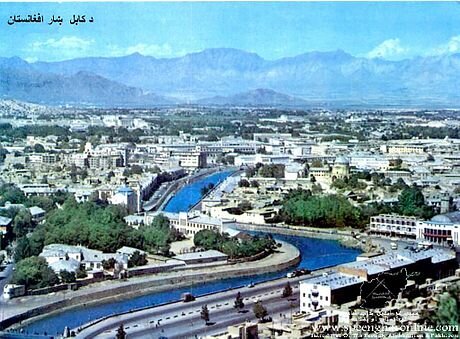

The city, before the Soviet occupation, in the mid-1970’s was a culture of traditional values ready to incorporate parts of western culture that encouraged a more open society. Kabul used to be a city with a graceful small city feeling that was making it's way towards what felt like an organic progression towards new possibilities before the Soviet Invasion in 1979.

Kabul City, Pre-Soviet Occupation

After 30 years of conflict and 15 years of development, these days, one can not drive around the capital city of Afghanistan and have a sense that all the international support for security has actually made Kabul safer, rather it has forced many internationals and Afghans to slowly leave due to ongoing conflict in parallel to an incohesive government and the current unemployment rate that has crippled the economy.

Driving through the city; the public streets are lined with blast proof metal doors, 14’ concrete blast resistant T-wall sections, checkpoint after checkpoint, and hesco’s. These militarized elements throughout the city has increasingly become the bulk of what one will confront throughout the city. Throughout the expatriaot community, there were two basic types of communities, people who viewed themselves as a target and lived in a high profile security compound, outfitted with blast proof wall, doors, window, cars, and police versus people who were viewed as a target but chose to live a low profile in a relatively “normal” life with the old mud/brick house, and sometimes a good reliable Toyota Corolla. It poses a question about whether this deeply militarized city is the product of an actual measure of threat or a measure of irresponsible planning by not addressing the major parts that would have made a large impact on the local economy and as a result the security situation. Kabul has just become more insecure as the years pass, exhausting the international and afghan community.

Present Kabul City

Within the urban plan of Kabul a boundary wall is an interesting thing. The traditional boundary wall, which has always been used in the urban plan as a cultural wall separating the public from private, is a mud wall in which integrates with the idea of an interior courtyard plan. The production of a military grade boundary wall is very costly and needs to be resistant and effective against blast pressure, fire and impact. One can spend more money on the promise that these things will make you “more safer” than the actually reality in certain cases. Both the traditional and military wall intends to separate and compartmentalize but one more extreme than the other. Possibly, since Afghans had previously understood the psychology of boundaries they now have adapted to the military walls and fortification to the point of also unconsciously accepting isolation and oppression. Eventually, advocating for a closed society.

One of the largest populations of people that were probably the most important to the future security of Afghanistan, was the local labor market that would have had an major impact on industry and urban planning. Tons of donor and mystery money went into buildings behind walls and major businesses able to afford a militarized compound. Overnight millionaires whom were winning government contracts, land owners selling because the real estate value went up astronomically, ministries that needed buildings, ministers that needed houses, embassies that needed embassies, ambassadors that needed ambassador grade housing, international guests that needed international level housing, multilateral organizations that needed live/work places, all built with top level security provisions. The city slowly became swallowed by the sudden wave of development. It came in too fast and contracts were devoured by business that had the expertise to handle, communicate and negotiate with the international donor community.

Kings Palace, Darlumand, post civil war

Recently, there has been interest by the Afghan government to restore an iconic palace opposite from a newly built parliamentary building in which is estimated as a 30 million dollar restoration project. This has been the mentality toward reconstruction, to focus on projects that are behind walls, partially because security is easier to manage removing it from the risk of a public street. There should be no question at this moment about the reconstruction of a palace. This project is an emotional response from the President’s office to rebuild a destroyed historical building. A city must address the most basic needs that are of major concern to the urban fabric first. Like the Kabul river and surrounding old city, shelter, housing, sewage and stormwater drainage and public space, to name a few. If Afghanistan had the chance to start slowly from the beginning by “facilitating” local afghan labor and industry the chance to solve there own problems the way they had been before the war, there would be less of a security problem today. Afghans have a history of resilience towards insecurity and opposition. If you give a person a job and a way to contribute to there communities, they will organically be apart of the security process. They would police and secure there own areas. Currently, there is a very weak link between government and the people. People are disappointed, dissatisfied and billions have gone into the wrong pockets. The majority is what holds the fabric of society together. The overarching plan from the beginning was too much, too fast and all at once.

If the Afghan labor force, had learned more skills, started a business and was able to build there own communities the way that they have doing so for decades, we might not of had all the high-rise and super-construction but a Kabul that would have remained modest for a few decades, enduring the rubble, and dealt with it’s problems from the ground up. To develop and support hundreds of local business to build thousands of new homes in the traditional mud-brick house construction facilitating local skill, labor and material, versus the thousands of concrete Pakistani style poppy-palaces that did not give back to the Afghan community, rather the Pakistan construction industry benefitted. Local skill, labor, and material is the core of any civilization wanting to uproot themselves and move towards economic and community stabilization. Facilitate Afghans to build the way they have for decades. Facilitate, support and endeavor to have faith people will eventually only protect and secure what they feel they have worked hard to achieve. Start small.